Welcome to the ninth edition of Civic Tech Monthly. Below you’ll find news and notes about civic tech from Australia and around the world.

It seems like October has been a busy month for everyone. All around the world people are flat-out launching new projects, presenting at conferences, and sharing plans and ideas. This edition is full of opportunities and ideas you can draw on.

As always we’d love to see you at the OpenAustralia Foundation Sydney Pub Meet next Tuesday in Sydney.

If you know someone who’d like this newsletter, pass it on: http://eepurl.com/bcE0DX.

News and Notes

Thank you Matthew

There must be something in the water because this has been a big year for changing leadership in civic tech organisations with Tom Steinberg moving on from mySociety and James McKinney from OpenNorth. This time it’s our very own co-founder Matthew Landauer.

So now it’s our turn to say thank you to Matthew. Since creating OpenAustralia.org.au over 7 years ago Matthew has worked tirelessly to better connect people with their communities, governments and politicians through his work at the OpenAustralia Foundation. While many people talk about this, Matthew just gets on and makes it happen. He’s done this by programming, designing and writing websites that have been used by millions of people, and by teaching and inspiring others to do the same as a leader in civic tech.

From Henare and Luke, thank you Matthew for everything you taught us. With Kat keeping our feet on the ground, we’ll continue to put what you taught us to work. We’re full steam ahead.

Apply for support and development help from mySociety

There are dozens of civic tech projects, running all over the world, built on mySociety’s open source work. They’re using platforms like Alaveteli, FixMyStreet, WriteInPublic or YourNextRepresentative.

You can get mySociety’s help to set up something like this in your area. For projects that suit their program, they’re offering technical and development help, as well as advice on a range of issues and even hosting.

Applications close October 30, so get in quick.

Democracy Club plans for 2016 UK elections

For the UK’s 2015 elections Democracy Club helped thousands of people in the UK vote and find out more about candidates. Now they’re laying down plans for their next round:

May 2016 will see a much wider range of elections in the UK – from local councils to city mayors, from police commissioners to the devolved assemblies and parliaments…

For May 2016, we’ve set ourselves the ambitious target of knowing about every candidate in every election in the UK…

And that’s not all. On 7 May, we noticed that one of the most popular internet searches was: “Where do I vote?” For that reason, among others, we think there’s real value to be gained in open data for polling stations – their locations and the areas they serve.

If you’ve got elections coming up in your area check out their plans and how they approach these projects. Maybe these ideas will inspire a project of your own, of course all their projects are open source for you to use.

Update to an Open Data Masters Thesis

In 2011 Zarino Zappia completed his Masters thesis on the state of “open data” use in the UK and USA: ‘Participation, Power, Provenance: Mapping Information Flows in Open Data Development’ [4MB PDF]. Early this month he posted some thoughts about what has and hasn’t changed since then touching on what government, hackers, non-profits, and the private sector are up to. It’s a wonderful and refreshingly honest appraisal of the state of open data.

New York Senate relaunches with a website designed for citizens

It’s great to see a legislature launch a website that has been designed to help citizens. There’s still lots of work to do, but it’s a big step ahead of what most people around the world get. How does nysenate.gov compare to your local senate or parliament’s website?

Legislative openness conference in Georgia brings together delegates from over 30 countries

You can now watch the sessions from the Government Partnership’s Legislative Openness Working Group meeting hosted by the Parliament of Georgia last month. There were over 75 parliamentary and civil society delegates from more than 30 countries present for the meeting.

You can find out more about what went down in OpeningParliament.org’s helpful review of the event.

Freedom of Information sketch diary

Myfanwy Tristram has posted her amazing sketches from AlaveteliCon 2015, the international conference on Freedom of Information technologies.

The sketches are a great introduction to the characters behind FOI projects around the world (including ours!). Myf gives you a real sense of the different flavour that each team brings to their common mission. The sketches are published over 5 posts on Myf’s blog.

An epic web scraping tutorial

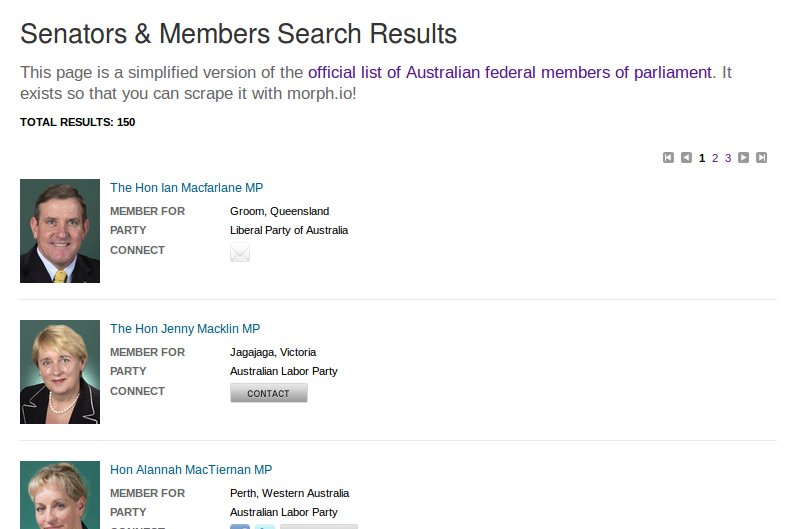

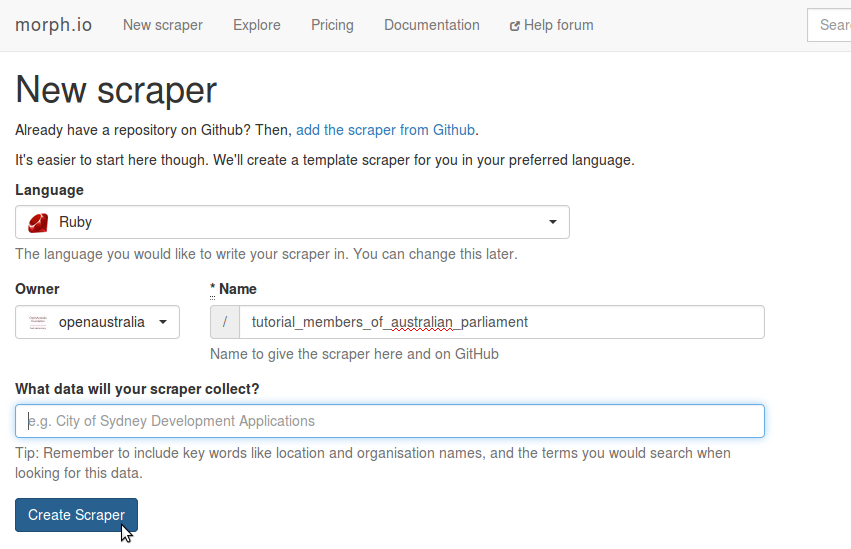

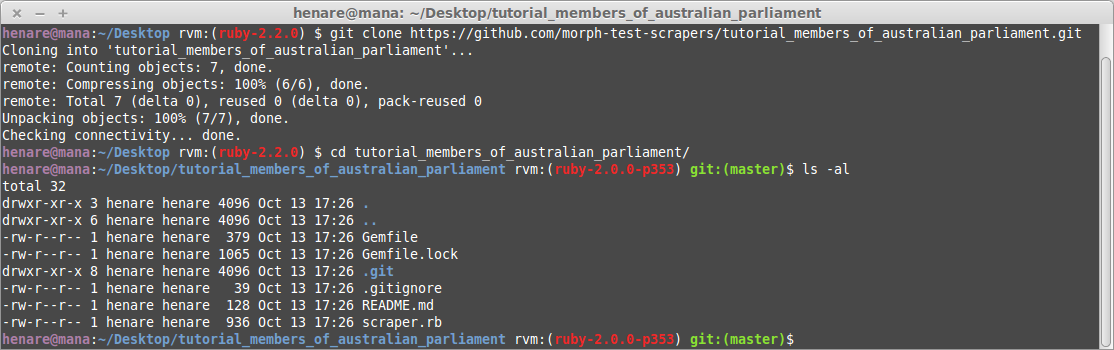

After our first scraping workshop last month we wrote up some of the things we learned. One of them was that a reference guide would have been useful. So Luke wrote an epic step-by-step tutorial on how to write a web scraper in Ruby using morph.io!

Over the last couple of weeks we’ve featured these in a blog post series in which you actually create, publish and run your own working scraper. Give it a try and let us know how you go. We’re keen to help more people get the skills to build the projects they want to see. Any feedback on the tutorial would be greatly appreciated.

If you’re in Sydney this weekend and keen to learn scraping, we’ve still got three spots available in our next Introduction to Web Scraping Workshop on Sunday. We’d love to you join us.

Videos from Code for America Summit

Code for America Summit was earlier this month and you can now watch it all online, including this much tweeted presentation from Tom Loosemore.

Who comments in PlanningAlerts and how could it work better?

About a month ago we started some design research to learn from the people who use PlanningAlerts how we can make the experience of commenting on local planning better. This post talks about how we’re approaching design research and our observations in this project so far.

We’ve currently working on a new project to help people write to their elected local councillors about planning applications. The aim is to strengthen the connection between citizens and local councillors around one of the most important things that local government does: planning. We’re also trying to improve the whole commenting flow in PlanningAlerts.

The Impacts of Civic Technology Conference 2016, call for papers

Speaking of research, the Impacts of Civic Technology Conference (TICTEC) is on again in 2016. TICTEC was a great success in 2015. It collected people from all over the world to talk and learn about research in civic tech and the impact that these projects make.

TICTEC 2016 will be 27th-28th April 2016 in Barcelona. The call for papers and workshop ideas is now open. mySociety also offer grants for travel and registration that you can also apply for now.

Who comments in PlanningAlerts and how could it work better?

In our last two quarterly planning posts (see Q3 2015 and Q4 2015), we’ve talked about helping people write to their elected local councillors about planning applications through PlanningAlerts. As Matthew wrote in June, “The aim is to strengthen the connection between citizens and local councillors around one of the most important things that local government does which is planning”. We’re also trying to improve the whole commenting flow in PlanningAlerts.

I’ve been working on this new system for a while now, prototyping and iterating on the new comment options and folding improvements back into the general comment form so everybody benefits.

About a month ago I ran a survey with people who had made a comment on PlanningAlerts in the last few months. The survey went out to just over 500 people and we had 36 responders–about the same percentage turn-out as our PlanningAlerts survey at the beginning of the year (6% from 20,000). As you can see, the vast majority of PlanningAlerts users don’t currently comment.

We’ve never asked users about the commenting process before, so I was initially trying to find out some quite general things:

The responses include some clear patterns and have raised a bunch of questions to follow up with short structured interviews. I’m also going to have these people use the new form prototype. This is to weed out usability problems before we launch this new feature to some areas of PlanningAlerts.

Here are some of the observations from the survey responses:

Older people are more likely to comment in PlanningAlerts

We’re now run two surveys of PlanningAlerts users asking them roughly how old they are. The first survey was sent to all users, this recent one was just to people who had recently commented on a planning application through the site.

Compared to the first survey to all users, responders to the recent commenters survey were relatively older. There were less people in their 30s and 40s and more in their 60s and 70s. Older people may be more likely to respond to these surveys generally, but we can still see from the different results that commenters are relatively older.

Knowing this can help us better empathise with the people using PlanningAlerts and make it more usable. For example, there is currently a lot of very small, grey text on the site that is likely not noticeable or comfortable to read for people with diminished eye sight—almost everybody’s eye sight gets at least a little worse with age. Knowing that this could be an issue for lots of PlanningAlerts users makes improving the readability of text a higher priority.

There’s a good understanding that comments go to planning authorities, but not that they go to neighbours signed up to PlanningAlerts

To “Who do you think receives your comments made on PlanningAlerts?” 86% (32) of responders checked “Local council staff”. Only 35% (13) checked “Neighbours who are signed up to PlanningAlerts”. Only one person thought their comments also went to elected councillors.

There seems to be a good understanding amongst these commenters that their comments are sent to the planning authority for the application. But not that they go to other people in the area signed up to PlanningAlerts. They were also very clear that their comments did not go to elected councillors.

In the interviews I want to follow up on this are find out if people are positive or negative about their comments going to other locals. I personally think it’s an important part of PlanningAlerts that people in an area can learn about local development, local history and how to impact the planning process from their neighbours. It seems like an efficient way to share knowledge, a way to strengthen connections between people and to demonstrate how easy it is to comment. If people are negative about this then what are their concerns?

“I have no idea if the comments will be listened to or what impact they will have if any”

There’s a clear pattern in the responses that people don’t think their comments are being listened to by planning authorities. They also don’t know how they could find out if they are. One person noted this as a reason to why they don’t make more comments.

Giving people simple access to their elected local representatives, and a way to have a public exchange with them, will hopefully provide a lever to increase their impact.

“I would only comment on applications that really affect me”

There was a strong pattern of people saying they only comment on applications that will effect them or that are interesting to them:

How do people decide if an application is relevant to them? Is there a common criteria?

Why don’t you comment on more applications? “It takes too much time”

A number of people mentioned that commenting was a time consuming process, and that this prevented them from commenting on more applications:

What are people’s basic processes for commenting in PlanningAlerts? What are the most time consuming components of this? Can we save people time?

“I have only commented on applications where I have a knowledge of the property or street amenities.”

A few people mentioned that they feel you should have a certain amount of knowledge of an application or area to comment on it, and that they only comment on applications they are knowledgeable about.

How does someone become knowledgeable about application? What is the most important and useful information about applications?

Comment in private

A small number of people mentioned that they would like to be able to comment without it being made public.

Suggestions & improvements

There were a few suggestions for changes to PlanningAlerts:

Summing up PlanningAlerts

We also had a few comments that are just nice summaries of what is good about PlanningAlerts. It’s great to see that there are people who understand and can articulate what PlanningAlerts does well:

Next steps

If we want to make using PlanningAlerts a intuitive and enjoyable experience we need to understand the humans at the centre of it’s design. This is a small step to improve our understanding of the type of people who comment in PlanningAlerts, some of their concerns, and some of the barriers to commenting.

We’ve already drawn on the responses to this survey in updating wording and information surrounding the commenting process to make it better fit people’s mental model and address their concerns.

I’m now lining up interviews with a handful of the people who responded to try and answer some of the questions raised above and get to know them more. They’ll also show us how they use PlanningAlerts and test out the new comment form. This will highlight current usability problems and hopefully suggest ways to make commenting easier for everyone.

Design research is still very new to the OpenAustralia Foundation. Like all our work, we’re always open to advice and contributions to help us improve our projects. If you’re experienced in user research and want to make a contribution to our open source projects to transform democracy, please drop us a line or come down to our monthly pub meet. We’d love to hear your ideas.